Coping Flexibility Is Essential to Our Resilience

From lab studies to lived experience, the principle of homeostasis explains why adaptability—not endurance—is the true foundation of resilience.

In my previous post, Stress Management 101: Principles Before Techniques, I introduced a key idea: effective stress management begins with principles, not methods. The most important of these is coping flexibility—the ability of both body and mind to adapt, rebalance, and recover when stress pushes them off center.

This follow-up explores how that principle plays out in practice—in the laboratory and in the unpredictable conditions of real life, where stress is anything but theoretical.

From Principle to Proof

In Stress Management 101, we saw that the body continually strives for homeostasis—returning to balance after challenge. The same applies to the mind: resilience depends less on any single strategy and more on the capacity to shift when circumstances change.

Psychologist Carolyn Schwartz and colleagues demonstrated this in a simple but revealing card-sorting study (1). Participants—healthy younger adults, a group of older adults with most having health conditions, and patients with chronic illness—chose coping “cards” for different stressful scenarios such as problem-solving, acceptance, or seeking support.

The pattern was clear: healthier adults drew from a wider range of strategies, tailoring their responses to the situation. Those facing greater physical or emotional strain tended to repeat the same few moves, even when they no longer fit.

The parallel is striking: just as illness can limit the body’s homeostatic flexibility, it can also narrow the mind’s coping repertoire. Adaptability—physical or psychological—is the hallmark of health: the ability to sense imbalance and restore stability.

From the Lab to Real Life

That’s the principle in theory—but what does it look like under real-world pressure? The COVID-19 pandemic offered a powerful test case.

During the height of the crisis, Dr. Kelly Wong, an emergency physician then 28, faced relentless physical and emotional strain. Yet instead of relying on a single form of relief, she built a diverse toolkit to sustain herself (2):

- Physical/Behavioral: Running and marathon training to discharge tension

- Cognitive/Emotional: Meditation and quiet reflection to reset her mind

- Engagement/Flow: Baking bread—an absorbing, creative outlet with tangible reward

- Social Connection: Smiling and greeting strangers to reinforce shared humanity

- Boundary Setting: Taking digital breaks to protect her attention and mood.

In a situation that would have narrowed most people’s coping range, Dr. Wong expanded hers—a real-time example of flexibility in action. She didn’t fight stress with force; she navigated it through adaptability—just as the principle of homeostasis predicts.

Building Coping Flexibility

The encouraging news is that flexibility isn’t fixed—it can grow stronger with practice.

Think of it like training as a boxer: you can study every punch, but until you step into the ring and practice, you can’t rely on it when it counts.

Coping responses work the same way. To handle stress effectively, you have to build your skills through repetition, awareness, and small adjustments over time—long before the real test arrives.

Step 1: Coping Awareness

Begin by observing your own patterns. Notice when your coping starts to narrow—when you default to the same familiar moves, whether that’s withdrawing, overworking, or trying to push through.

When stress or fatigue constricts your range, you become mentally rigid—less open to new perspectives and less able to pivot when circumstances change. Recognizing that rigidity is the first step in reversing it.

That moment of awareness opens the door to choice, and choice is where flexibility begins.

Step 2: Expanding Your Range

Once you can see your patterns, start exploring what’s missing from your toolkit.

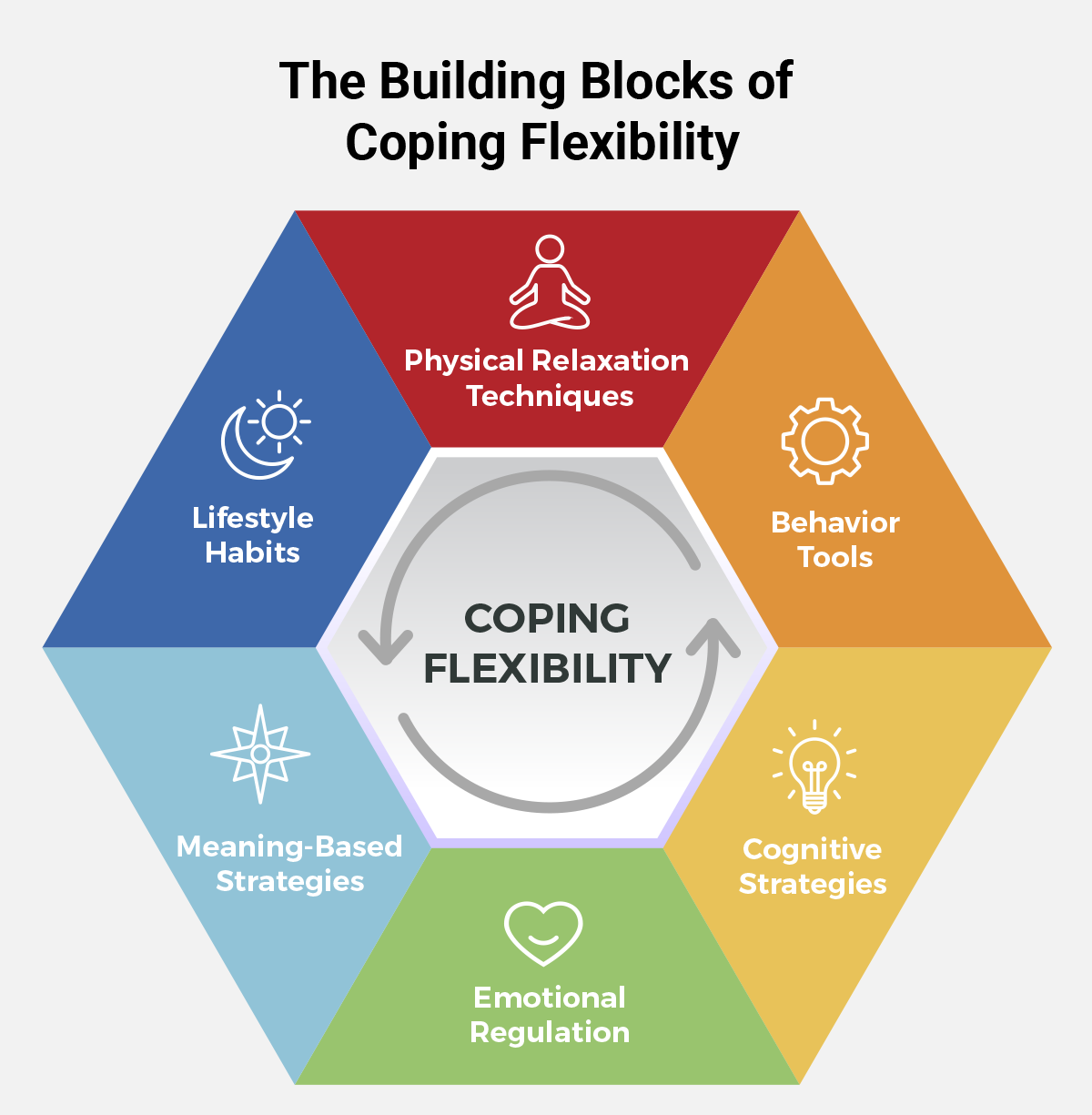

In another previous post, I described six broad “buckets” of coping strategies—physical relaxation, behavioral action, cognitive reframing, emotional regulation, meaning-based approaches, and lifestyle habits.

Flexibility grows when we draw from multiple coping sources

Take a page from Dr. Wong, who intentionally drew from multiple buckets to stay balanced under pressure. Ask yourself: which dimensions do I lean on too heavily, and which ones could I strengthen?

Then, choose one new coping response to experiment with—just one.

Maybe it’s adding a short relaxation break (physical), reframing a recurring worry (cognitive), writing down what you’re grateful for (emotional), or setting a new boundary, like saying no to a draining commitment (behavioral).

Practice your new coping move in calm, low-stakes moments so that when stress intensifies, it’s already part of your inner rhythm—the way you naturally return to balance.

Turning Practice into Resilience

Each new tool you add brings a twofold benefit: it gives you more effective ways to meet stress head-on, and it expands your coping flexibility, undoing the rigidity that stress creates. Flexibility isn’t just a coping strategy—it’s how the mind stays supple.

Over time, this becomes the quiet engine of resilience: not the absence of stress, but the confidence that you can regain your footing again, whatever the challenge.

And when life finally deals you a high-stakes hand, you’ll be ready—not scrambling for a single move, but playing with a full deck.

References

- Schwartz CE, Peng CK, Lester N, Daltroy LH, Goldberger AL. Self-reported coping behavior in health and disease: assessment with a card sort game. Behavioral Medicine. 1998; 24: 41–4.

- Valdesolo F. Five Ways to Relieve Stress During the Coronavirus Pandemic. The Wall Street Journal, April 6, 2020.